Monday, November 21, 2005

Obour: Ne Ho Ye Hu Hu Hu Hu

I met Obour on several occasions while in Ghana. For a time, I knew him when he was living in Commonwealth Hall at University of Ghana, Legon. So far he is the only hiplife artist in the public spotlight that's got a university degree.

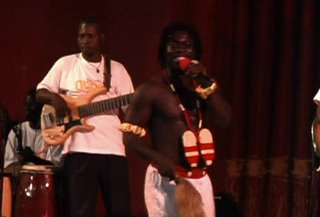

Obour is huge, simply put. A couple years ago he embarked on a nationwide tour, which no hiplifer had done before. He launched a quality website, also a first for Ghana's rappers. Now Obour is bringing the live band into hiplife for arguably the first time. There is a belief that having a backing band, as opposed to a sequenced electronic groove, would help hiplife gain international recognition. After sweeping the Ghana Music Awards this year, Obour is firmly placed at or near the top of commercial hiplife in Ghana right now.

Click here or on the post title above to check out Obour's unparalleled website.

I mentioned a song in a previous post about a tadpole causing a huge raucous among the public and media. This song, "Konkontibaa" by Obour, simply observes that although young now the tadpole will grow up to big and strong like its mother one day. Through a series of clever metaphors and proverbial speech, Obour weaves a more than five minute impression which parallels plenty of sexual allusions, most of which relate to older men going after young girls. While this phenomenon is well-known and discussions on the issue in the media abound. Why did/do people make such a big deal out of a song that may or may not be "profane."

When asked, Obour usually denies that the song is glorifying, or even mentioning, chasing teenage girls. The fact of the matter is, the lyrics are so complex and subtle that most listeners would not realize just how bad they were until they really sat down examined them. It took me and a Ghanaian friend more than three hours to decipher the words and put them into a semi-intelligible English translation. Even then, the potency of Obour's allusions and proverbs were lost in translation. At the end of it all my friend could only exclaim in an almost surprised tone, "It's profane, it's very profane!"

I would reproduce the translation here, but it still needs a lot more work. Hopefully in the near future...

Here are my notes about my first meeting with Obour. After the notes is a bit of the transcript of our discussion. Obour talks about how he got into music, why hip-hop is so important to Ghanaian youth, and what his music is all about. He also sheds some light on what is going to be an ongoing issue on this blog: How are hiplife and hiphop are perceived by different levels of society, and why?

02/11/04

Obour-Commonwealth Hall Room A10, 9:30 am

I knock twice and wait. Is he going to be here, or did I come all this way for nothing (again)? Last week I came at around 10 am and stayed for three hours with Roro, Obour’s personal assistant, watching Kill Bill, drinking Coke, and chatting in Obour’s room. I met his roommates and realized he is just a regular guy having fun at school.

This time is different, I can hear someone moving inside. After a couple minutes, Obour comes to the door in his boxers. He said I didn’t wake him up and that I can come in. A cute girl emerges quietly, regally from the back room. Obour (short, stout, dreads, smiling) welcomes me and seems quite relaxed despite having been interrupted. I try to make a good impression.

The dorm room is small with an attached room that’s even smaller, which is where Roro stays. Roro is taking a year off from school to work with Obour. He is basically a good friend who helps keep the public a certain distance from Obour when necessary. He answers the phone and organizes appointments for Obour.

The room is hot, so I begin to sweat. No one seems to care or notice because despite there being two fans within view, no one turns them on. I am used to people in Ghana pandering to my every need, but these guys aren't like that.

Obour is studying music and sociology. He says he has one year left. The reason he says he didn’t show up last week for our agreed meeting time is that he had a make-up lecture. Obour’s been working a lot playing shows and making appearances, so he has been missing some classes.

When did you start with music?

Most people would say from birth actually, yeah, because yeah, from childhood I used to sing at church and everything. Music as a profession really got into me around ‘99, that’s when I started recording albums actually.

So you recorded your first album in ’99?

Yeah.

And is that one still around?

Yeah, it’s still around. And, I mean, it’s what brought me to the game actually. It has a local slang that goes like, Obour, …, it means fiercesome one.

And what does Obour mean?

Stone. That’s the literal meaning. Stone, like a hard one.

So what about rap, your first album that you put out was hiplife?

Yeah, it was hiplife, because that was the trend then. Hiplife was what was going on. Actually, we all used to do music, then in Ghana the type of music that was going on was raga. That was the good days of [groups]... That was the trend of the day, everywhere you go that was what was going on. But when hiplife took off, when we started doing our own thing in Twi, then the first time somebody got that on record and started selling it. [inaudible] this could be a profession, this could be something we could do then all the guys then it was myself, the Ex-Doe's, the VIP's, the Nananom's. This is like ’96 thereabout. Then we were like, “Charlie, we can really do something with this business, we can do something. Then I was at secondary [school] so I couldn’t do much, but when I passed out of secondary in ’99, then I recorded my album.

As far as hiphop, I mean, how did you get into hiphop in the first place?

I feel like when you give up the talent, I mean, sometimes I write songs and gospel music comes up. But it’s to do more with where you think the interest lies the most. I mean, for gospel music I feel like one day I might do a—but mostly I do gospel songs on my album. Every album that I have there’s a gospel song, there’s a song dedicated to God on the album. And I feel in my own small way, I’m more talented in the hiplife field, that is, talking deep Twi and [inaudible] more than I am in gospel or in hiphop or whatever…

Why is hiplife so popular in Ghana?

I think it’s because the youth is upholding it, I mean, it’s the youth that keeps everything happening wherever you are. If something is happening and it doesn’t have the backing of the youth, I feel it is really difficult to implement because it’s the same youth who demonstrate, who do all that. Hiplife has the full support of the youth, so I think that is why hiplife is so popular now.

Why do you support it, personally?

I felt at least finally we were getting something of our own that had a light of internationalism, so it's something that could register Ghanaian music somewhere on the globe. So why not give it all the support?

Before Reggie Rockstone the youth had no voice?

Yeah, it’s true.

Can you talk about that?

Yeah, I mean, then it was more of the highlife type of music and all that the youth used to do in life was hiphop. I mean, Tupac, yeah, Snoop Doggy…that was the voice of the youth then, now we have a voice of our own. I felt we needed it. We all needed it. We were all looking for the way to really break into the scenes of Ghanaian music. It was highlife, [Daddy] Lumba, Kojo Antwi, that’s all it was about. But when we all got it, and everybody was making an effort. And finally, the first effort Reggie Rockstone made created a big impact. We were like, “Wow, the door’s open now let’s all enter”…

I guess Snoop’s not talking about things that really matter here (in Ghana)…So, what do you talk about in your songs?

Hiplife takes trends, actually, it depends on the musician. Personally, me, I talk on diverse issues, I mean, sometimes on an album you can have me talking about maybe six or ten issues. A typical Obour album will definitely have maybe about two songs that are of Ghanaian originality. I may take one of the cultures of Ghana, should it be maybe the Akans or the Fantes, and do a song typically on that culture. That’s one song you would find on a typical Obour album. Then you definitely find a song that talks about life at that particular point. If it’s stressful, I talk about it being stressful; if it’s getting better, I will talk about it getting better. I mean it’s a little political actually. And then you will have me talking about love per se. What is going on in my love life, I might relate it to everybody. And then, I will also have something that talks about the the Black, the Black African. I mean, my perception about the Black. Every album, you get me talking about something about the Black. If witchcraft is what is worrying us, I’ll say it; if it’s the color that’s worrying us, I’ll say it; if it’s the perception that we don’t like to go to school and all, I’ll say it, I mean. So, that’s how a typical Obour album looks like, I touch on diverse issues.

So how do people seem to respond to these things? Do they find it controversial?

Yeah, most of my songs, they think are controversial, but, yo, if you don’t get controversial, you don’t get people talking about you. Most people think I am controversial. I talk on issues that the pastors might be afraid to talk about. I mean, even the issues that the politicians and ministers won’t want to talk about. You get me touching on them. Quite recently I released a song that people are really taking their own type of motive for it. It’s more like, what is going on these days. What I see around me, is what I talk about. These days in Ghana, I see old men going after young girls. And I felt I should talk about it, and I just talked about. And it’s really making a little impact.

That is why it’s music, actually, because I will always leave it to the public to define it. My own meaning to that song, if I should tell what motivated me to even do that song, you might not have an idea. But it’s good when people hear songs and they create their own impressions. I mean, that’s why it should be music. I fit into the music in this way. I feel I am young and I will still grow, so I should do it; I feel I am old and I like young girls. I mean, that’s it. Everybody fits into it the way he or she wants to fit in…

What about the youth’s use of hiphop culture?

That is more copying what hiphop is like. Hiplife, in a way, from the founding fathers, they took inspiration from hiphop. So indirectly, hiplife takes bits and pieces of hiphop culture. So hiplife is kind of basically, what the founding fathers see it is like hiphop, given a different name, because it is written in a different tongue back home. I mean, that’s all it is about. So whatever hiphoppers do—apart from the Ghanaian culture does not allow any Ghanaian to be using swear words and talking deep, deep trash and profanity and sexually suggestive lyrics and all. I mean, maybe in hiphop you can just sing a song like [sings a bit of Salt n Pepa's “Let’s Talk About Sex”]. But in Ghana, you can’t go like that because the code of ethics and morals doesn’t allow it. So maybe those are the portions of hiphop that we are leaving behind. I mean, hiphop you can get a fellow brother pulling a gun, shooting at one another. But in hiplife you wouldn’t get that also because the morals of the Ghanaian society doesn’t allow that. But the other portion, that is the fashion of hiphop, I think hiplife also takes to the fashion. The way that in hiphop you don’t get them playing live band. And that is what happens in hiplife as well, you don’t play live band. They play their beat and they toast, they DJ, they breakdance…it’s all pieces of hiphop that hiplife has [inaudible].

What about the music itself?

When hiplife came up at first, it had stolen the beat rhythm of hiphop. But I think in the first or two years, it started taking a different phase. I think I was one of the contributing factors of making the thing change in a way, When hiplife took off, it was more like hiphop beat, with a Twi or with a local dialect. That was how hiplife took off. And then, the old folks in Ghana were more used to the highlife rhythms actually. So, that’s why they weren't giving hiplife the support. “What type of music is this? I mean, you’re singing white music, I mean white rhythms, and,you’re just singing in Twi.” They weren’t giving hiplife the support.

When a few hiplife musicians decided to take the rhythms of the local people, take highlife rhythms, use the hiphop culture on it, ride on the rhythm like you would have ridden on it if it was a hiphop beat, and see how it turns out to be. And when we did it like that, at least then the older folks also saw more it like what was of their own. At least it’s just like they played highlife rhythms, except this time the kicks were more harder like it is in hiphop. There wasn’t too much strings to make it sound too archaic. I mean it was more of a deeper type of music, a stronger type of music that’s you, but still has bits and pieces of the local thing that the old age want to hear. And so, hiplife beat-wise has really—it’s just like hiphop: I mean hiphop, you can just hear an Indian tone, an Indian type of rhythm, it’s been written on a hiphop type of rhythm and it’s happening, you get people liking it. You can get [inaudible] playing an African type of beat, totally African, [makes sound of drum], totally African, and they still like it.

And that is what is happening in hiplife now. You can get somebody riding on a strictly hiphop beat and people will like it. The next thing you hear is somebody riding on a totally local African, Ghanaian type of beat and they still eat it up. So, hiplife now rhythm-wise is diverse. You can’t really classify hiplife like you would classify Francophone music. I mean, when you hear to Francophone music, you should be sure you are going to hear your guitars [makes high-pitched guitar sound], I mean, it’s not like you classify rock music as you can get your strong rock guitars. But hiplife, you can’t really classify the rhythm now because it has taken the trend of how hiphop is. You can’t classify the hiphop rhythm, I mean, you will definitely have a kick, but you can still get one loud hiphop punk doing something that is full of strings. I mean, talk of Nas, Nas did a song with Tupac, which was more of strings. You can’t classify that as hiphop, but it’s hiphop.

What is the current public perception of hiplife?

Yeah, so the current perception is more like now you get so many old people falling into how we wanted them to fall into. You get so many old people appreciating the hiplife more than their own music they were used to because we were able to kind of lobby them into our sector. I should think if hiplife were to change its course now I think would still like it because now—first, first they were pulling away from hiplife because they thought we were talking too fast, they can’t hear the lyrics, and also on top of it too the beat is Western so they didn’t like it. And then what we did was we introduced more of local beats and we still talked fast and they were like, “Yeah, these days these hiplife musicians, at least now they play highlife rhythms, so we like it.” And now you still get them liking hiplife that even doesn’t have the old pieces, they don’t have the rhythms they want. But, because they are getting used to hiplife, now at least when we rap they can hear. Now they even like hiplife for the lyrical content these days. Because, I mean, you get more hiplife artists—some people have decided to be comic on the microphone. So, if you listen to them you just have to laugh. You’ll be hearing funny things from track one to track ten. And for that matter, some people like hiplife. It’s a platform that you can use to say more things than if you sing in highlife…