Saturday, June 10, 2006

Hiplife Videos on YouTube

These were most likely ripped from a VCD bootleg collection of popular hiplife "clips," the kind you would buy off a guy selling them out of his backpack or a wodden kiosk in virtually any town in Ghana.

"Ahomka Womu" - VIP

VIP's classic cut, "Ahomka Womu," one which you should definitely know about. The song combines old school highlife in a really tasteful way, making it one of the biggest tracks in the last few years. The first couple verses of rhymes are dead-on with catchy phrasing. A relatively interesting video, especially near the end when the trio of rappers/singers have a 70s flashback moment complete with matching suits and afros.

The majority of music video directors in Ghana stay away from ironic or conceptual themes. There are some notable exceptions, though.

King Luu is one of the most ambitious directors in Ghana today. He has been in the business since it started back in the mid-90s, putting together over the years countless memorable clips for hiplife, gospel, and highlife artists.

"Adua No Ebu," the big-budget, high-concept video he shot for masters of irony Nkasei a few years back, exemplifies King Luu's vision. With a clip, he wants to tell a story, Luu told me one afternoon. "Adua No Ebu" depicts the slave trade in Africa and is set on a green mountain far from the homes of the urbanite rappers and production staff.

There is nothing on the web (yet) in regards to "Adua No Ebu," but the video is considered a classic. It features Reggie Rockstone to boot, who does a verse in English. The song is critical of colonialism and the post-colonial mentality. I may eventually post excerpts of my interviews about the song with the members of Nkasei and video director King Luu.

"Toffee" - Castro

This is Castro ("the Destroyer"). He's a big star now that this song is played fifty million times a day on the radio. Catchy nonetheless, using Congolese bass and drums riddim courtesy of celebrity engineer J-Que. "Toffee" is a King Luu video.

Enjoy.

"Ahomka Womu" - VIP

VIP's classic cut, "Ahomka Womu," one which you should definitely know about. The song combines old school highlife in a really tasteful way, making it one of the biggest tracks in the last few years. The first couple verses of rhymes are dead-on with catchy phrasing. A relatively interesting video, especially near the end when the trio of rappers/singers have a 70s flashback moment complete with matching suits and afros.

The majority of music video directors in Ghana stay away from ironic or conceptual themes. There are some notable exceptions, though.

King Luu is one of the most ambitious directors in Ghana today. He has been in the business since it started back in the mid-90s, putting together over the years countless memorable clips for hiplife, gospel, and highlife artists.

"Adua No Ebu," the big-budget, high-concept video he shot for masters of irony Nkasei a few years back, exemplifies King Luu's vision. With a clip, he wants to tell a story, Luu told me one afternoon. "Adua No Ebu" depicts the slave trade in Africa and is set on a green mountain far from the homes of the urbanite rappers and production staff.

There is nothing on the web (yet) in regards to "Adua No Ebu," but the video is considered a classic. It features Reggie Rockstone to boot, who does a verse in English. The song is critical of colonialism and the post-colonial mentality. I may eventually post excerpts of my interviews about the song with the members of Nkasei and video director King Luu.

"Toffee" - Castro

This is Castro ("the Destroyer"). He's a big star now that this song is played fifty million times a day on the radio. Catchy nonetheless, using Congolese bass and drums riddim courtesy of celebrity engineer J-Que. "Toffee" is a King Luu video.

Enjoy.

Saturday, April 29, 2006

Neighborhood Folk

Some places I've been reading of late (in no particular order):

-Naija Jams is your spot for info on music in Nigeria, usually hip-hop related. If you didn't hear about it last year, read about the 50 Cent's run-in with local rap star Eedris at an airport, which casued 50 to end his tour prematurely.

-Africanhiphop.com remains the central and most vital source of information on hip-hop across the continent. This cat from Holland has been running the site for years now. He mainly does a lot of research and work with Tanzanian artists.

-Benn loxo du taccu is the best African mp3 blog I know of. Matt knows his stuff!

-Also, if you're a big dork like me and still hungry for more, check African-rap.com for the latest info on African hip-hop news and events in Europe.

For those with adventurous ears and fewer Afrocentric tendencies:

-Check Woebot for thoughtful articles on everything from rare-ass vinyl to French prog and other stuff you've probably never heard of (that's good).

-Funky 16 Corners is a way daunting collection of rare funk and soul 45s with comprehensive descriptions.

-Cocaine Blunts is downright vital for rap/hip-hop heads looking for mp3s and commentary on the rappers/producers you know and love and the underground artists you wish you knew about earlier.

I have been doing an mp3 blog of sorts myself called Awesome Tapes from Africa. You'll find the occasional hiplife cut there, along with a bunch of weird and/or amazing music I have come across. Tapes must never be forgotten.

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Peace in Dagbon, Northern Ghana?

BBC report here describes the recent funeral for the murdered King of Dagbon. Four years ago he and twenty or so of his men were slain by the rival clan vying for the throne.

Tamale, the town I've been blogging about recently, is largest town in the Dagbon traditional area in the Northern Region. Although the actual capital of the kingdom is in Yendi, a several hours down the road, Tamale is largest Dagomba town.

This BBC article is a bit sensationalist at times. But useful in gaining a broader sense of the context in which some young musicians are making serious strides.

Just check out the last few posts for more on hiplife in Northern Ghana.

Tamale, the town I've been blogging about recently, is largest town in the Dagbon traditional area in the Northern Region. Although the actual capital of the kingdom is in Yendi, a several hours down the road, Tamale is largest Dagomba town.

This BBC article is a bit sensationalist at times. But useful in gaining a broader sense of the context in which some young musicians are making serious strides.

Just check out the last few posts for more on hiplife in Northern Ghana.

Monday, April 17, 2006

A Snapshot of Popular Music in Tamale

There are so many musicians doing creative things in Tamale, Northern Region, Ghana. I wanted mention just a couple of them. Hopefully, there be time in future to devote to talking about more of these singular local artists.

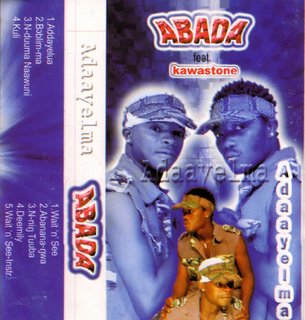

I met Abada when they played a VCD (yeah, that's right. that's what's often used in Ghana) release party for one young hiplife group called B.F.G.s. Their name, which stands for Big Friendly Guys, subverts the stereotypes amongst ordinary folks that hiplife dudes are trouble. This is the first Tamale hiplife artist to release a VCD, so this show was big. Abada were part of a line-up that included most of the top Tamale musicians of the last several years. The show and after-show lasted til late. At least 10 different groups and individuals performed a mix of hiplife, their local brand of highlife, and reggae. The parking lot outside was a sea of motorbikes and ice cream sellers and all sorts of local teens. Most people ended up at another place on the other side of town where there were DJs spinning the usual mix of r&b, hip-hop, dancehall, and local sounds.

Abada, interviewed at their hang-out. An area they call Yaari ghetto. Black Moon on the right, Black Shanty on the left

Here they are on stage at the release party the night before. This is at one of the main nightlife spots in town, Picorna.

Black Moon, the the sweeter, highlife-oriented half of the vocal duo.

Black Shanty, the ragga boy with the rough and deep tones.

MC Rauf, aka Shoe Shine Boy, is one of the well-established veterans of the scene these days. I met him when I first came to Tamale in 2002 and we chatted at his barbershop. He was initially a shoe shine boy, he told me. To be a shoe shine boy is one of least desirable or profitable gigs in Ghana, but it also connotes a sort of dilligence, which Rauf seems to embody. Listen to one song, aptly titled "

I was lucky to come back to Tamale after about three years and kick it with Rauf again.

Sunday, April 09, 2006

Gyedu-Blay Ambolley and the Roots of Hiplife

One of the first questions I would ask anyone in Ghana that I interviewed was, "When did you first hear someone rap in a local language?" If I could take all the footage I shot and make one massive montage of people giving their three-word answer, it would last at least five minutes.

Gyedu Blay-Ambolley.

Reggie Rockstone is almost universally recognized as the first really rap in a clear adaptation of hip-hop aesthetics. He was the first to do something referred to by the indignenized moniker, hiplife. But, the first Ghanaian musician to "rap"-- to speak quickly using rhyme, metaphor, and other poetic and/or verbal devices-- was Gyedu-Blay Ambolley (according to the people with whom I spoke).

So, it follows that we check out what is arguably the first use of rap in Ghana on a record (that I know of at least). The song is called"Highlife". It's essentially Burger highlife (a sort of disco-infused higlife which emerged in the late-1970s), with its four-on-the-floor groove, synths, and English lyrics. This recording comes from the consistently impressive Cut Your Coat LP (1985).

This excellent site offers more info on Ambolley and Ambolley's own site is homebase proper for sure...enjoy.

I traded records with a guy in Accra, that's where I got this record. I gave him a stack of vinyl, which included Nas' Illmatic, The Listening by Little Brother, and the "Blue Flowers" 12", and he gave me this and a few other highlife, juju, and afro-beat LPs. His name is Nii and he's a really great guy. If you want to trade records/DJ equipment with a guy in Ghana, contact me and I'll link you up.

Gyedu Blay-Ambolley.

Reggie Rockstone is almost universally recognized as the first really rap in a clear adaptation of hip-hop aesthetics. He was the first to do something referred to by the indignenized moniker, hiplife. But, the first Ghanaian musician to "rap"-- to speak quickly using rhyme, metaphor, and other poetic and/or verbal devices-- was Gyedu-Blay Ambolley (according to the people with whom I spoke).

So, it follows that we check out what is arguably the first use of rap in Ghana on a record (that I know of at least). The song is called

This excellent site offers more info on Ambolley and Ambolley's own site is homebase proper for sure...enjoy.

I traded records with a guy in Accra, that's where I got this record. I gave him a stack of vinyl, which included Nas' Illmatic, The Listening by Little Brother, and the "Blue Flowers" 12", and he gave me this and a few other highlife, juju, and afro-beat LPs. His name is Nii and he's a really great guy. If you want to trade records/DJ equipment with a guy in Ghana, contact me and I'll link you up.

Thursday, April 06, 2006

Hip-Hop Is Big In Mali

A wall near the town football stadium, Mopti, Mali

A wall on a building near the university, Timbuktu, Mali

A wall on a building near the university, Timbuktu, Mali

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

They Use Rap To Sell Alcohol in Africa Too

Most musicians in Ghana, even some of the most famous ones, don't make tons of money. They have to pay bills, so many appear in advertisements if they can.

Click here to see this commercial a seriously seminal rapper did with a local drink company. (Go to the Media Room and click on the third video)

This is not an isolated case. Another key forefather of the movement told me he made more money on a single ad contract with a major beer company than he did in his whole career in music. My previous post makes mention of hiplifers and adverts.

So, why not go for some real money in endorsements? Why not, when you're minor (in many cases) fiscal stake in your music prevents you from making the kind of cash you probably deserve?

Most hiplife artists sell the rights to their record outright to a producer in order to get it printed and onto the market. The artist gets a chunk of cash. But even if the song sells a lot, they don't see too much more money, unless they play lots of shows.

Click here to see this commercial a seriously seminal rapper did with a local drink company. (Go to the Media Room and click on the third video)

This is not an isolated case. Another key forefather of the movement told me he made more money on a single ad contract with a major beer company than he did in his whole career in music. My previous post makes mention of hiplifers and adverts.

So, why not go for some real money in endorsements? Why not, when you're minor (in many cases) fiscal stake in your music prevents you from making the kind of cash you probably deserve?

Most hiplife artists sell the rights to their record outright to a producer in order to get it printed and onto the market. The artist gets a chunk of cash. But even if the song sells a lot, they don't see too much more money, unless they play lots of shows.

Monday, April 03, 2006

GhanaConscience Breaks Down Sidney's "Obia Nye Obia"

Here you'll find a thorough article on Sidney's most recent status-quo-perturbing cut, "Obia Nye Obia." The article is written from the perspective of someone in Ghana, hearing all the back and forth of arguments for and against the song's message, a message that seems to have polarized folks.

It's business as usual for Sidney, whose earlier controversial work includes "Scenti No" and "Abuskeleke." The former is a metaphor-laden ode to the various smells found around Accra, some of which originate in the Parliament house and/or the MP's armpits. The latter talks of young girls and their bodies, which can be used by men to a point (for a price, of course) but are eventually theirs (and only theirs) take elsewhere. Abuskeleke is a commonly-used, though uncouth, slang term basically meaning slut, to simplify translation. Not sure which came first the song or the associated term.

Long story short, Sidney talks about issues that stir up public discussion. Read the above-linked article about his "Obia Nye Obia" and check out the vital lyricist that is Sidney the "Hiplife Ninja."

Check out GhanaConscience, which is part of GhanaThink.org. They have an enormous database of lyrics to Ghanaian songs, including lots of hiplife stuff. That's where I found this awesome article.

PS- I wish I had a photo of the huge billboards advertising Champion Condoms in Ghana. Sidney is on there endorsing this popular brand, lurking over bus stations and traffic circles around the country. They had radio commercials which Sidney raps on to the beat of "Scenti No," only this time he inserts "Champion Condoms" in there somewhere...

Sunday, April 02, 2006

Hammer Makes Serious Beats

This is Hammer. He is known for beats that, on the surface, borrow more from Western-style hip-hop than they do from Ghanaian dance rhythms and folk songs. But, if you listen closely, you can hear local sensibilities.He is conscious of Akan tradition rhythms such as Adowa when he composes his beats. This contrasts with J-Que’s (see previous post) sound in many ways, not least because J-Que’s jama is a Ga rhythm. Like Wulomei in the '70s, J-Que has sparked a Ga cultural revival through his consistent use of a rhythm they consider to be their own. Actually a number of other groups in Ghana lay claim to jama, but we won't get into that here.

Tympani, orchestra chimes, and minor keys feature strongly in Hammer's productions, while most beat programmers stick to your usual synthesized trumpet and organ timbres. Hammer acknowledges his penchant for a driving pulse that usually hangs somwhere around 112 BPM. This is faster than States-side hip-hop tends to be. Don’t forget, we’re still in Ghana, where music generally needs to be danceable if anyone’s going to buy it or spin it.

With a sound that has influenced a significant number of beat programmers in Ghana, Hammer still somehow feels like a cult phenonmenon almost. Since he refuses to work with artists who can't rap hard over a beat or freestyle acapella, he is not quite as prolific as some of the other top engineers in Accra. You don't hear his beats for five songs in a row on the radio (this can happen with a couple other engineers/producers). His work is instantly recognizable and the rappers who bless his tracks are some of the most hardcore in Ghana, though not necessarily the most rich and famous.

Hammer works almost exclusively with local-language rappers. Known for his work initially with Twi rapper Obrafuor, and later with Tinny, Hammer encourages virtuosic skills. He is credited with pushing Tinny, one of Ghana's biggest rappers, to begin rapping in what was then considered an unconventional language, Ga. Tinny's Ga rhymes blow people away with their clever twists and pointed remarks. Ga is the language spoken by the original inhabits of what is now Accra, Ghana's capital. But, the vast majority of Ghanaians cannot understand speak Ga, even many of those who live in Accra. Only now, with the popularity of Tinny, and more recently, Castro, I found people rocking Ga hiplife songs all over Ghana, even in the Twi stronghold of Kumasi and all the way in the Upper East Region. Ga language has gained a sort of hip cachet amongst young people in the smaller urban centers of Ghana, being that it has become associated with big city life and several huge hiplife songs whose lyrics reflect fast and fun times. This all comes (indirectly) thanks to the support and collaboration of Hammer.

Ground breaking work with Obrafuor, along with a series of compilations, have laid the foundations for a counter-movement of hiplife artists who don't care much for the bubblegum arrangements and lovey-dovey lyrics found in many mainstream jams. Rather, Hammer and his camp of young rappers bring the only hint of locally produced edginess that can be found on most local radio stations. Nevertheless, innumerable English-language emcees sporting hard beats and conscious rhymes continue to languish in almost complete obscurity...

Nurturing underground rappers is the new trend among the hiplifers who have already reached a certain level of success in the industry. Hammer oringinated this trned with his series of Compilations, which drawn on the talent of underground cats who've made their way into Hammer's camp. It is though these comps that underground rappers likeKwaw Kesse and Okra Tom became well-known over the last couple years.

Hammer was one of the first people I contacted when I reached Ghana, and he became a sort of touchstone for me throughout my year of research. He was the first person to invite me to Hush Hush to observe a recording session. Hammer also introduced me to a number of players in the industry. Much respect to Hammer, a very humble, down-to-earth, and talented individual.

Sunday, March 05, 2006

An Interview With J-Que, Hiplife's Leading Producer

J-Que's sound is ubiquitous. He is everywhere. The following interview certainly finds him sounding a bit cocky at times, but this is with good reason: He is only a exaggerating a little when he says 80% of the song played on the radio are his productions.

After introducing a hiplife interpretation of traditional dance rhythm, jama (or dzama), several years ago, J-Que has transformed hiplife. No longer can people easily argue hiplife has nothing Ghanaian in it. Generally understood to be a Ga rhythm, jama is used by people around the country, especially at football matches, where there are bands in the stands playing along to support their team. For those of you familiar with Latin American music, the skeletal basis for jama is very similar to the 3-2 clave rhythm found in many genres from that part of the world.

Today, the rap heard on the radio and on TV, the mainstream stuff, is produced by J-Que. Increasingly, though, J-Que's music may very well be the soundtrack to which so many Ghanaian youth live life. And, now that the elders are taking a serious liking to the traditional dance rhythms infused in the music, J-Que and his jama have become almost universal. Even cats up north are using jama rhythms in their songs.

J-Que is the most sought after, most imitated producer no doubt. But there are a lot of people who don't like him, his music, and his attitude. he seemed like a real guy to me, but others have accused him of a lot of drama. Haters abound. After all, how many dudes in Ghana get to drive a turqouise BMW?

Below are excerpts from a long conversation with J-Que where he talks about his approach to music, the fans who love it, and the future of hiplife. He also discusses hiplife as a way to boost Ghana's international musical reputation. He truly believes that without his indigenized production style, hiplife would be lost and without a clear future.

11/19/04 at Hush Hush Studios

I arrive around 6:30pm to meet J-Que (Jeff Quaye) and find him in the studio, working with a reggae singer. He says hi quickly and tells me to sit down and wait a few minutes. He works through Pro Tools briskly and takes care of the finishing touches on the track he’s working on.

I am surprised when I meet J-Que because I imagined him to be bigger and maybe more “hip-hop”-looking. I later learned that this expectation is common. J-Que is actually smallish, clean cut, and rather looks like an average dude. You could easily mistake him for someone else on the street. But once he began talking, I could see that he had a kind energy. One that made it easy to listen to him speak.

J-Que takes me to a different, smaller room where there is a girl (hiplife artist, Mzbel) watching TV. We kick her out and sit down to talk. He seems comfortable and confident, dressed smart but simple.

So, why, with your extensive musical background, do you do hiplife?

I mostly do hiplife music because that is what the public are into, the Ghanaians like it now and I have done hip-hop way back and stuff, but I don’t do those things any more. I don’t want to play hip-hop, I don’t want to play reggae. The reason being that, you know, when I am working, when I come to the studio to work with a client and the client sings to me and I listen to what the client is singing, I always make sure that every beat I produce have a representation of our national flag in it. That is me. Every beat I put out should represent Ghana, if not, it should have some Ghanaian feel to it.

So, if you listen to the music I do, if I am playing ragga or whatever, I have my congas and my shakers and my cowbells. These things are from Africa, these things are indigenous instruments that we have here in Africa. Every beat that I do I make sure that I have the national flag of Ghana in mind. And the reason why I do that is I also realized that most Ghanaians, you know, in Ghana, our music is not going international. People are just getting to hear about hiplife.

Now one reason, my point of view, the reason why it is not going international: In Ghana here, Ghana is a small country, but everybody’s playing all kinds of music here in Ghana. You have people playing reggae, you have people playing hip-hop, some people are even playing jazz, you have rock, you have all these things here in Ghana. But if you look outside Ghana, like Jamaica, if you go to Jamaica, if they are not playing reggae, they are playing dancehall. That is what everybody plays. If everybody decides to play his national music, that is the only way our music can go international. You know, but then, if you are in your country, you have your traditional and cultural music and you are playing somebody’s music, there is no way your music can go far. So the reason why I am playing this jama or like introducing this thing is that that is the only way I think we can have our music represented in the international showbiz market. If Ghanaians doing hiplife, gospel everybody decides to play their own form of music rather than gospel or hip-hop. Because you know you can’t play hip-hop more than Dr. Dre or Timbaland. No way you can do that. Assuming there is a world music festival, Ghanaians are there, Americans are there, Jamaicans are there, and somebody comes from American everybody expects them to do hip-hop or R&B or something, from Jamaica you know reggae or dancehall, the moment they call Ghana Africa, they are coming to play something cultural, you know, something that represents Africa…

… I am one of the guys who’s sustaining our culture, who is holding our culture, who is keeping it going. So if I also decide to leave and the rest of the guys decide to play hip-hop and things, then what has Ghana got [inaudible], it has got nothing. So, I researched more into instruments that [are from] Africa, that are made from Africa. I have researched more into those instruments. There are instruments sometimes when I research I haven’t seen them before, I don’t even how they sound. So, I want to go on vacation, when I go on vacation, I’ll go to places in Africa. I see instruments that I don’t even know how they sound, to go sample them, bring them to my studio, edit it and then use them in my production. If you listen to every track that I produce, you know, in Ghana here when they hear a track they want to know it’s me. The moment you hear the conga, you should know this is J-Que. I have it in all my tracks…I also have my name in almost all my tracks…

What about the future of hiplife?

I think hiplife really has a future. If they see it the way I am seeing it. If not kpanlogo, you know, Ghana we have highlife, the Northerners have their music, you know, we have various forms of traditional music in Ghana. If hiplife would be played based on the Ghanaian cultural way, a little, you know, like 20% hip-hop and then the 80% would be dominated on our traditional music, then hiplife will really go very, very far. But then if we don’t play it like that—you know, it would surprise you that I have a lot of enemies and player-haters because of the style I have introduced. Because of the style I am playing, most of the hiplife guys you know, they are thinking-- You know, hiplife started with hip-hop. When we started playing hiplife we were playing it in the form of hip-hop, we look onto the hip-hop beats. Sometimes we sampled the same beat and made them sing onto it. You know, because of the rap, we were looking more into the hip-hop vein. Because of the rap they were doing in Twi. So we looked at the rap they did and we supplied the same kind of beat, which was wrong, which was very, very, very, it was wrong koraa [Twi = at all, totally]. But we didn’t know, we didn’t know at all. You know, some people, because of what I have introduced, they don’t even want to see my face. People go on radio, they diss me, they insult me. This guy has changed the trend. This guy is not doing hiplife anymore. Hiplife is now on another level, they don’t like it. We want this way. But that is wrong, that is wrong at all. So, you know, if we play it the hip-hop way, we don’t have a future. But then if we play it in our own traditional form of music, that is the only way we can go far.

So then you now see hiplife as something quite distinct musically?

…Someone told me that I am the first guy who has given identity to hiplife. You know, hiplife is now different. It has an identity. Most people don’t know, but what I am doing is I am giving identity to it. So, you can really differentiate hiplife from hip-hop. You know, they are all rapping. Rap is rap, whether you rap in Twi, whether you happen to rap in English. But then, the rhythm behind it. You know, for the Americans, they play the hip-hop. For us, for it to look like us, we have to play our cultural music. It could be highlife, it could be the jama that I have introduced, it could be adowa, it could be anything. Then we can really say that this is distinct, this is different from—but now hiplife is different for me, to me hiplife-- I can say that hiplife has a future. Because now, if you listen to radio, I don’t know if you listen to radio, if you listen to when they play highlife, they shift to hiplife, 80% of the songs they play are my productions. Which means that hiplife has a future.

Look at all these guys outside [the studio, Hush Hush], everybody here wants to come and work. I am even closing at 10 and they know I am closing at 10, but they all have a hope that at least I will spend 30 minutes with them. You know, Hush Hush here, we run three sessions a day. We work 6[AM] to 2[PM]. That is the morning session. Then the afternoon session is 2 to 10. And then, the night session is 10[PM] to 6[AM]. If I work everyday, and then, most days I work two sessions every day. Because of my work—you wouldn’t believe it. As of now, I am working with almost every artist in Ghana. Most of the guys-- I have to release 35 artistes before Christmas. You wouldn’t believe it. I can’t sleep. I am always here. I spend all of my time here in Hush Hush. When I get home the only thing I can do is sleep. Formerly I was working on weekends, but this time I have stopped working on Saturdays and Sundays because the workload is just too much. So this should tell you that hiplife is really getting somewhere.

And the guys--I have also realized, with the introduction of jama and kpanlogo that I am playing, people like it, so they all want to come, come and work. Even tracks that are hitting on the market that I didn’t play, it’s jama, if you don’t play it the way I play it, there is no way they will accept it. “Konkontiba” [Obour’s smash hit last year]. Most people think I did it, but I am not the one who did “Konkontiba.” I like the engineer who worked on it because he is very good. If he had played it in any other vein…Morris Babyface, he won last year’s engineer of the year. Last year he won. If he had played it in any other way, it wouldn’t hit.

There’s one style that I am introducing now, I want to talk a little about it. What I realized is, if you look at our movies, if you study the movies, I realize that the Nigerian movies have taken over our industry. We don’t have any good Ghanaian movies to boast of and to match the Nigerians. So, if we are not careful, their music too will come and take over our music. So I listened a little to Nigerian music and, you know, I said, “No, there is a way I can fuse hiplife with their form of music.” So, I have also introduced that style, and that is like Afro-Pop. I have introduced that one. So if you listen to what I did for Obour, “Shine Your Eye,” featured a Nigerian, Baba Ashanti. If you listen to that track, you’ll realize that track’s different from what I have been doing. I also did the same style for Dr. Poh, he’s a new artist. The song is “Na Hu Ko Sa.” And it’s doing well in Nigeria. I also realized I am introducing this too. So that before their music also comes to take over, no we have it already mixed with ours. There’s no way they can take over our music industry. Our songs are doing well. The Obour song like this is doing well in Lagos.

I did the remix for Tic Tac, the one he did with Tony Tetuila. Ghanaians now they are getting to understand the remixes, you know remixes is not usual of we Ghanaians. But then remixes got popular because—you know, some people go and record their music some way. I don’t have any problem with—I like –I really recommend that if an artist is coming to work, he works with more than one engineer, at least have different flavor on your album. J-Que does a little, Hammer does a little, Morris, Zapp… You know, what happens is, sometimes, they record their hits from other engineers. They will realize that when their song comes on the market, then the song doesn’t do well. They will be tempted to bring it to me to do a remix. Basically now, I am doing lots of remixes. You know I have lots of remixes from other engineers that produced it. And I am proud to say that I don’t produce a track and it will go to another engineer for a remix. That has never happened, it will never happen. What I say when I go on TV, the other engineers should buck up, they should also do their work very well. Because there’s no way that I will work for someone else to bring it to correct it. They should also make that when they are working, nobody should bring their work to me. For remixes, I charge more. The song is already spoiled. You have to do more than what the person did originally. So for remixes you have to work harder than-- if it is a new song, you don’t have any challenge. You just do your thing. You know, but then if it is not a new song and its been done already, it’s done good, you have to improve on it you have to work double. So for remixes I take almost twice the money I take for original songs. That is about that one too.

Did the youth in Ghana have no voice before Reggie Rockstone came in ‘94?

Before Reggie came, you know, hiplife, people were doing hiplife. The boys were doing that, but then, nobody had taken the risk to come out with hiplife. So nobody wanted to come out—what they were doing was, when you go to shows, you see the people rap, they’re on the stage rapping, singing, and stuff. No people were singing before Reggie came out with hiplife. That is a mistake he is doing. There are some guys here, they don’t even have producers, they don’t have demos, but they can really sing, they come and sit here every day hoping that somebody will talk to them to ask them, “Are you a singer?” And if you put these guys behind a microphone, you’d be surprised to hear what they can do, they can really sing. But the fact that they don’t have platforms to show it doesn’t mean, you know-- so if Reggie made that statement I think he’s wrong because there are people who are really doing this thing are I know some people who had demos when Reggie came out they still have their demos, they’ve not secured producers, they’ve not secured producers. In hiplife what we see—the introduction of the new artists, it’s more, you hear more of the new artists coming out than the old artists. We always have new artists, new artists, they are always flooding the market. I think they are also doing well…right now competition is really healthy because if you think you the big boy, you have four albums, and you sit home and—trust me, where is [Lord] Kenya now, where is Reggie, where are these people now? There is this group, they’ve really maintained their stance, Buk Bak, you know? They have their fifth album on the market and they have always maintained their stance. Obrafour has always maintained his stance. VIP, when I worked with them on their first album. After their first album, they were working with other engineers and nobody heard of them. It was when they came back with the one I just did…the guys if you are not careful they will just over take you like that…look at Batman, Batman is a new artist, Madfish is a new artist.

So what is the music scene doing for the youth?

Music now is really helping the youth. Because you know in Ghana, most of the people don’t have money to continue their education. Some of them don’t even have an education background at all. Most of them see hiplife (laughs), or the music scene, as a venture for them to easily make it. If you call a shoeshine boy and you chat with him: “So why are you doing this thing?” “Oh, I want to save money to go and record with J-Que.” When you talk to these ice water boys: “What are you doing?” “Oh, I want to go and record.” They come to me. Sometimes we charge them. Ok, let’s say, this is thousand, I am taking thousand cedis. I have hundred cedis, keep it for me. They will go they, will come, they will go, they will come. Yes, that is what they do. Until they have their thousand and then they will definitely come and do it.

The reason why this is happening, you know, in Ghana now, the executive producers, they don’t go to the studio with the artists to record them, they buy the music. So if you are an artist, you have to record your own music. That is what happens in Ghana now. You have to record your own music. Mastered, not demo, before he would listen, for him to produce the secondary. For him to listen to your song you need to have your master. All the guys you see here, they are guys who are trying to record their master by themselves. So I think the music scene has created some kind of job opportunity for the youth, in fact a lot of the youth now are into hiplife. If you look at hiplife, almost all the guys are youths.

What if you spend all your savings on a recording and find no producer?

That is the problem. Some people have had their master. You know all the figures are not the same. Some people have luck following them. Some people will just come, they will do a song, they will take it out, and they will get a producer to come and finish the rest. Some people will do a master and they won’t find anybody to come. For that one it happens, people have master recorded--I think even in America that happens...

After introducing a hiplife interpretation of traditional dance rhythm, jama (or dzama), several years ago, J-Que has transformed hiplife. No longer can people easily argue hiplife has nothing Ghanaian in it. Generally understood to be a Ga rhythm, jama is used by people around the country, especially at football matches, where there are bands in the stands playing along to support their team. For those of you familiar with Latin American music, the skeletal basis for jama is very similar to the 3-2 clave rhythm found in many genres from that part of the world.

Today, the rap heard on the radio and on TV, the mainstream stuff, is produced by J-Que. Increasingly, though, J-Que's music may very well be the soundtrack to which so many Ghanaian youth live life. And, now that the elders are taking a serious liking to the traditional dance rhythms infused in the music, J-Que and his jama have become almost universal. Even cats up north are using jama rhythms in their songs.

J-Que is the most sought after, most imitated producer no doubt. But there are a lot of people who don't like him, his music, and his attitude. he seemed like a real guy to me, but others have accused him of a lot of drama. Haters abound. After all, how many dudes in Ghana get to drive a turqouise BMW?

Below are excerpts from a long conversation with J-Que where he talks about his approach to music, the fans who love it, and the future of hiplife. He also discusses hiplife as a way to boost Ghana's international musical reputation. He truly believes that without his indigenized production style, hiplife would be lost and without a clear future.

11/19/04 at Hush Hush Studios

I arrive around 6:30pm to meet J-Que (Jeff Quaye) and find him in the studio, working with a reggae singer. He says hi quickly and tells me to sit down and wait a few minutes. He works through Pro Tools briskly and takes care of the finishing touches on the track he’s working on.

I am surprised when I meet J-Que because I imagined him to be bigger and maybe more “hip-hop”-looking. I later learned that this expectation is common. J-Que is actually smallish, clean cut, and rather looks like an average dude. You could easily mistake him for someone else on the street. But once he began talking, I could see that he had a kind energy. One that made it easy to listen to him speak.

J-Que takes me to a different, smaller room where there is a girl (hiplife artist, Mzbel) watching TV. We kick her out and sit down to talk. He seems comfortable and confident, dressed smart but simple.

So, why, with your extensive musical background, do you do hiplife?

I mostly do hiplife music because that is what the public are into, the Ghanaians like it now and I have done hip-hop way back and stuff, but I don’t do those things any more. I don’t want to play hip-hop, I don’t want to play reggae. The reason being that, you know, when I am working, when I come to the studio to work with a client and the client sings to me and I listen to what the client is singing, I always make sure that every beat I produce have a representation of our national flag in it. That is me. Every beat I put out should represent Ghana, if not, it should have some Ghanaian feel to it.

So, if you listen to the music I do, if I am playing ragga or whatever, I have my congas and my shakers and my cowbells. These things are from Africa, these things are indigenous instruments that we have here in Africa. Every beat that I do I make sure that I have the national flag of Ghana in mind. And the reason why I do that is I also realized that most Ghanaians, you know, in Ghana, our music is not going international. People are just getting to hear about hiplife.

Now one reason, my point of view, the reason why it is not going international: In Ghana here, Ghana is a small country, but everybody’s playing all kinds of music here in Ghana. You have people playing reggae, you have people playing hip-hop, some people are even playing jazz, you have rock, you have all these things here in Ghana. But if you look outside Ghana, like Jamaica, if you go to Jamaica, if they are not playing reggae, they are playing dancehall. That is what everybody plays. If everybody decides to play his national music, that is the only way our music can go international. You know, but then, if you are in your country, you have your traditional and cultural music and you are playing somebody’s music, there is no way your music can go far. So the reason why I am playing this jama or like introducing this thing is that that is the only way I think we can have our music represented in the international showbiz market. If Ghanaians doing hiplife, gospel everybody decides to play their own form of music rather than gospel or hip-hop. Because you know you can’t play hip-hop more than Dr. Dre or Timbaland. No way you can do that. Assuming there is a world music festival, Ghanaians are there, Americans are there, Jamaicans are there, and somebody comes from American everybody expects them to do hip-hop or R&B or something, from Jamaica you know reggae or dancehall, the moment they call Ghana Africa, they are coming to play something cultural, you know, something that represents Africa…

… I am one of the guys who’s sustaining our culture, who is holding our culture, who is keeping it going. So if I also decide to leave and the rest of the guys decide to play hip-hop and things, then what has Ghana got [inaudible], it has got nothing. So, I researched more into instruments that [are from] Africa, that are made from Africa. I have researched more into those instruments. There are instruments sometimes when I research I haven’t seen them before, I don’t even how they sound. So, I want to go on vacation, when I go on vacation, I’ll go to places in Africa. I see instruments that I don’t even know how they sound, to go sample them, bring them to my studio, edit it and then use them in my production. If you listen to every track that I produce, you know, in Ghana here when they hear a track they want to know it’s me. The moment you hear the conga, you should know this is J-Que. I have it in all my tracks…I also have my name in almost all my tracks…

What about the future of hiplife?

I think hiplife really has a future. If they see it the way I am seeing it. If not kpanlogo, you know, Ghana we have highlife, the Northerners have their music, you know, we have various forms of traditional music in Ghana. If hiplife would be played based on the Ghanaian cultural way, a little, you know, like 20% hip-hop and then the 80% would be dominated on our traditional music, then hiplife will really go very, very far. But then if we don’t play it like that—you know, it would surprise you that I have a lot of enemies and player-haters because of the style I have introduced. Because of the style I am playing, most of the hiplife guys you know, they are thinking-- You know, hiplife started with hip-hop. When we started playing hiplife we were playing it in the form of hip-hop, we look onto the hip-hop beats. Sometimes we sampled the same beat and made them sing onto it. You know, because of the rap, we were looking more into the hip-hop vein. Because of the rap they were doing in Twi. So we looked at the rap they did and we supplied the same kind of beat, which was wrong, which was very, very, very, it was wrong koraa [Twi = at all, totally]. But we didn’t know, we didn’t know at all. You know, some people, because of what I have introduced, they don’t even want to see my face. People go on radio, they diss me, they insult me. This guy has changed the trend. This guy is not doing hiplife anymore. Hiplife is now on another level, they don’t like it. We want this way. But that is wrong, that is wrong at all. So, you know, if we play it the hip-hop way, we don’t have a future. But then if we play it in our own traditional form of music, that is the only way we can go far.

So then you now see hiplife as something quite distinct musically?

…Someone told me that I am the first guy who has given identity to hiplife. You know, hiplife is now different. It has an identity. Most people don’t know, but what I am doing is I am giving identity to it. So, you can really differentiate hiplife from hip-hop. You know, they are all rapping. Rap is rap, whether you rap in Twi, whether you happen to rap in English. But then, the rhythm behind it. You know, for the Americans, they play the hip-hop. For us, for it to look like us, we have to play our cultural music. It could be highlife, it could be the jama that I have introduced, it could be adowa, it could be anything. Then we can really say that this is distinct, this is different from—but now hiplife is different for me, to me hiplife-- I can say that hiplife has a future. Because now, if you listen to radio, I don’t know if you listen to radio, if you listen to when they play highlife, they shift to hiplife, 80% of the songs they play are my productions. Which means that hiplife has a future.

Look at all these guys outside [the studio, Hush Hush], everybody here wants to come and work. I am even closing at 10 and they know I am closing at 10, but they all have a hope that at least I will spend 30 minutes with them. You know, Hush Hush here, we run three sessions a day. We work 6[AM] to 2[PM]. That is the morning session. Then the afternoon session is 2 to 10. And then, the night session is 10[PM] to 6[AM]. If I work everyday, and then, most days I work two sessions every day. Because of my work—you wouldn’t believe it. As of now, I am working with almost every artist in Ghana. Most of the guys-- I have to release 35 artistes before Christmas. You wouldn’t believe it. I can’t sleep. I am always here. I spend all of my time here in Hush Hush. When I get home the only thing I can do is sleep. Formerly I was working on weekends, but this time I have stopped working on Saturdays and Sundays because the workload is just too much. So this should tell you that hiplife is really getting somewhere.

And the guys--I have also realized, with the introduction of jama and kpanlogo that I am playing, people like it, so they all want to come, come and work. Even tracks that are hitting on the market that I didn’t play, it’s jama, if you don’t play it the way I play it, there is no way they will accept it. “Konkontiba” [Obour’s smash hit last year]. Most people think I did it, but I am not the one who did “Konkontiba.” I like the engineer who worked on it because he is very good. If he had played it in any other vein…Morris Babyface, he won last year’s engineer of the year. Last year he won. If he had played it in any other way, it wouldn’t hit.

There’s one style that I am introducing now, I want to talk a little about it. What I realized is, if you look at our movies, if you study the movies, I realize that the Nigerian movies have taken over our industry. We don’t have any good Ghanaian movies to boast of and to match the Nigerians. So, if we are not careful, their music too will come and take over our music. So I listened a little to Nigerian music and, you know, I said, “No, there is a way I can fuse hiplife with their form of music.” So, I have also introduced that style, and that is like Afro-Pop. I have introduced that one. So if you listen to what I did for Obour, “Shine Your Eye,” featured a Nigerian, Baba Ashanti. If you listen to that track, you’ll realize that track’s different from what I have been doing. I also did the same style for Dr. Poh, he’s a new artist. The song is “Na Hu Ko Sa.” And it’s doing well in Nigeria. I also realized I am introducing this too. So that before their music also comes to take over, no we have it already mixed with ours. There’s no way they can take over our music industry. Our songs are doing well. The Obour song like this is doing well in Lagos.

I did the remix for Tic Tac, the one he did with Tony Tetuila. Ghanaians now they are getting to understand the remixes, you know remixes is not usual of we Ghanaians. But then remixes got popular because—you know, some people go and record their music some way. I don’t have any problem with—I like –I really recommend that if an artist is coming to work, he works with more than one engineer, at least have different flavor on your album. J-Que does a little, Hammer does a little, Morris, Zapp… You know, what happens is, sometimes, they record their hits from other engineers. They will realize that when their song comes on the market, then the song doesn’t do well. They will be tempted to bring it to me to do a remix. Basically now, I am doing lots of remixes. You know I have lots of remixes from other engineers that produced it. And I am proud to say that I don’t produce a track and it will go to another engineer for a remix. That has never happened, it will never happen. What I say when I go on TV, the other engineers should buck up, they should also do their work very well. Because there’s no way that I will work for someone else to bring it to correct it. They should also make that when they are working, nobody should bring their work to me. For remixes, I charge more. The song is already spoiled. You have to do more than what the person did originally. So for remixes you have to work harder than-- if it is a new song, you don’t have any challenge. You just do your thing. You know, but then if it is not a new song and its been done already, it’s done good, you have to improve on it you have to work double. So for remixes I take almost twice the money I take for original songs. That is about that one too.

Did the youth in Ghana have no voice before Reggie Rockstone came in ‘94?

Before Reggie came, you know, hiplife, people were doing hiplife. The boys were doing that, but then, nobody had taken the risk to come out with hiplife. So nobody wanted to come out—what they were doing was, when you go to shows, you see the people rap, they’re on the stage rapping, singing, and stuff. No people were singing before Reggie came out with hiplife. That is a mistake he is doing. There are some guys here, they don’t even have producers, they don’t have demos, but they can really sing, they come and sit here every day hoping that somebody will talk to them to ask them, “Are you a singer?” And if you put these guys behind a microphone, you’d be surprised to hear what they can do, they can really sing. But the fact that they don’t have platforms to show it doesn’t mean, you know-- so if Reggie made that statement I think he’s wrong because there are people who are really doing this thing are I know some people who had demos when Reggie came out they still have their demos, they’ve not secured producers, they’ve not secured producers. In hiplife what we see—the introduction of the new artists, it’s more, you hear more of the new artists coming out than the old artists. We always have new artists, new artists, they are always flooding the market. I think they are also doing well…right now competition is really healthy because if you think you the big boy, you have four albums, and you sit home and—trust me, where is [Lord] Kenya now, where is Reggie, where are these people now? There is this group, they’ve really maintained their stance, Buk Bak, you know? They have their fifth album on the market and they have always maintained their stance. Obrafour has always maintained his stance. VIP, when I worked with them on their first album. After their first album, they were working with other engineers and nobody heard of them. It was when they came back with the one I just did…the guys if you are not careful they will just over take you like that…look at Batman, Batman is a new artist, Madfish is a new artist.

So what is the music scene doing for the youth?

Music now is really helping the youth. Because you know in Ghana, most of the people don’t have money to continue their education. Some of them don’t even have an education background at all. Most of them see hiplife (laughs), or the music scene, as a venture for them to easily make it. If you call a shoeshine boy and you chat with him: “So why are you doing this thing?” “Oh, I want to save money to go and record with J-Que.” When you talk to these ice water boys: “What are you doing?” “Oh, I want to go and record.” They come to me. Sometimes we charge them. Ok, let’s say, this is thousand, I am taking thousand cedis. I have hundred cedis, keep it for me. They will go they, will come, they will go, they will come. Yes, that is what they do. Until they have their thousand and then they will definitely come and do it.

The reason why this is happening, you know, in Ghana now, the executive producers, they don’t go to the studio with the artists to record them, they buy the music. So if you are an artist, you have to record your own music. That is what happens in Ghana now. You have to record your own music. Mastered, not demo, before he would listen, for him to produce the secondary. For him to listen to your song you need to have your master. All the guys you see here, they are guys who are trying to record their master by themselves. So I think the music scene has created some kind of job opportunity for the youth, in fact a lot of the youth now are into hiplife. If you look at hiplife, almost all the guys are youths.

What if you spend all your savings on a recording and find no producer?

That is the problem. Some people have had their master. You know all the figures are not the same. Some people have luck following them. Some people will just come, they will do a song, they will take it out, and they will get a producer to come and finish the rest. Some people will do a master and they won’t find anybody to come. For that one it happens, people have master recorded--I think even in America that happens...

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

This Guy Makes Some Fine Points (Thanks GhanaMusic.com)

This letter by a regular dude goes to show just how far hiplife (and the Ghanaiam music industry in general) has to go before people are happy.

[I found this article and lot of other timely, relatively accurate info from GhanaMusic.com, by far the best website about Ghanaian music imaginable. The guys who run it are pretty chill too.]

Right now, no one seems to be happy. Not the musicians, not the producers, not the fans, not even the radio DJs (who are probably making the most money out of the whole movement).

MUSIGA, Ghana's musicians' union, and a few other musician/artist groups, have suffered from power struggles, in-fighting, and corruption, not to mention the lack of a solid plan on how to deal with hiplife. After all, a great many of the union's members are traditional, highlife, gospel, and reggae musicians. Few hiplifers are involved. But this is changing to some extent, as some of the bigger names' managers and producers are connected to the larger network of powers in the industry who makes sure things basically remain the same. There are some less-than-transparent processes involving royalties collection and distribution. Let's just leave it at that for now...

Maybe just one example, if you like.

Payola, which is money paid to DJs to spin your music, is commonly noted as being a central factor crippling the industry. The letter linked above basically gets to the point: there's something serious flawed with the system of how music gets heard in Ghana, and this ultimately affects the quality of the music. If people pay the DJ to play sub-par music, people will get used to the music and eventually create music like it in hopes of also being heard.

Some people in the industry were also complaining that the top stars have become lazy and complacent. They know they can put out a certain level of record and it will "hit," so they rarely attempt to take things further, musically or conceptually. They will usually get paid a pre-determined amount by their executive producer for the rights of the recording outright.

This is clearly happening in some cases. How else to explain the relatively shallow slope of improvement in production over the past years? They should have tons of money from the record CDs they claim to sell and big shows they play outside of Ghana. Hey, I thought all those big guys (Obour, VIP, Tic Tac) were loaded with cash?!

Not the case...More on that soon to come.

[I found this article and lot of other timely, relatively accurate info from GhanaMusic.com, by far the best website about Ghanaian music imaginable. The guys who run it are pretty chill too.]

Right now, no one seems to be happy. Not the musicians, not the producers, not the fans, not even the radio DJs (who are probably making the most money out of the whole movement).

MUSIGA, Ghana's musicians' union, and a few other musician/artist groups, have suffered from power struggles, in-fighting, and corruption, not to mention the lack of a solid plan on how to deal with hiplife. After all, a great many of the union's members are traditional, highlife, gospel, and reggae musicians. Few hiplifers are involved. But this is changing to some extent, as some of the bigger names' managers and producers are connected to the larger network of powers in the industry who makes sure things basically remain the same. There are some less-than-transparent processes involving royalties collection and distribution. Let's just leave it at that for now...

Maybe just one example, if you like.

Payola, which is money paid to DJs to spin your music, is commonly noted as being a central factor crippling the industry. The letter linked above basically gets to the point: there's something serious flawed with the system of how music gets heard in Ghana, and this ultimately affects the quality of the music. If people pay the DJ to play sub-par music, people will get used to the music and eventually create music like it in hopes of also being heard.

Some people in the industry were also complaining that the top stars have become lazy and complacent. They know they can put out a certain level of record and it will "hit," so they rarely attempt to take things further, musically or conceptually. They will usually get paid a pre-determined amount by their executive producer for the rights of the recording outright.

This is clearly happening in some cases. How else to explain the relatively shallow slope of improvement in production over the past years? They should have tons of money from the record CDs they claim to sell and big shows they play outside of Ghana. Hey, I thought all those big guys (Obour, VIP, Tic Tac) were loaded with cash?!

Not the case...More on that soon to come.

Monday, February 20, 2006

Dusty, Heavily Islamic Northern Ghana: Hip-Hop Up There?

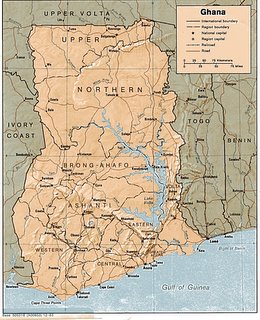

Ghana is a big country. Well, it's actually not that big (it's only about the size of Pennsylvania or Oregon), but it has a whole lot of distinct regional flavors for sure. Most of the music discussed on The Hiplife Complex comes from the southern third of the country. Most of the major cities are there, down by the coast in most cases. But what about the rest? What does life sound like up there in the North?

Things are quite different in Northern Ghana. The air is dry. It's usually quite hot. And, the landscape is sparsely occupied by a mix of scrawny trees, fields of yams, which are individually planted in little conical mounds, and round houses built sporadically in clustered compounds. Northern Ghana is home to most of the country's Muslims. Linguistically and culturally, this part of the country has more in common with Burkina Faso and Southern Mali. But, thanks to Africa's colonial legacy, this region belongs to Ghana, and therefore reflects an enormous amount of Ghanaianness, no matter how you cut it.

Not surprisingly, there's enough localized hip-hop, hiplife, and reggae up there to warrant a full investigation. So that's what I did. Beginning with my first foray into the North in 2002, a larger town called Tamale to be exact, I made friends with a whole crew of musicians and artists. Intertwining the sounds and styles of Greater Ghana eminating from urban centers Accra and Kumasi (located 8 and 12 hours down the road respectively) with the long-standing sensibilities distinctive of their Sahel-side region, these artists are consciously creative whilst lying at the fringe of Ghana's commercial music industry. Although some of Tamale's musicians have numerous albums to their credit, pack clubs around the region, and can be heard on all the radio stations in the area, the vast majority of their songs have never been heard (much less heard of) by the rest of Ghana.

Why the separation between Northern and Southern music/musicians?

It's a long story that I certainly don't have down pat, but, for starters, the British underdeveloped that part of the territory from the very beginning of colonialism. While the area beginning at the coast to just north of Kumasi (more or less the center of Ghana) was valuable in terms of resources like gold, bauxite, and timber, the dusty North was not a big concern. While the south became peppered with churches and schools and railways and roads, the North was left to itself. Islam took hold and long-standing socio-linguistic closeness to peoples of Burkina, Mali, and Togo kept Northern Ghanaians in a completely different bag, creatively and aesthetically. It was only later, as Ghana built up nationalistic steam during the post-independence period of the late-50s and early 1960s, that northern towns like Tamale, Bolgatanga, and Wa were reallyincluded in the new and diverse identity of Africa's first post-colonial nation-state.

Once Ghana had galvanized as a country, cultural and artistic concepts from the populous southern ethnic groups like the Asante and Ewe became dominant. So, Northerners heard highlife music from early on. They saw concert parties perform in remote Northern villages, as groups from Accra and Kumasi would travel far for audiences in those days. But the people of the three Northern regions (part of Ghana's 10 region system) had their own performance genres and traditions, not mention languages, religious practices, and family systems. At the time, Northerners (I use "Northerners" for expediency's sake, there are many distinct groups in the North) were creating and consuming a vast pallate of praise music, traditional dances, and even their own interpretations of popular highlife and foreign styles. Through Ghana Broadcasting Corporation, founded in 1935, everyone in Ghana theoretically had access to the same sounds. Of course, for people in the rural north, where there were few radios, there was less contact with cosmopolitan musical movements.

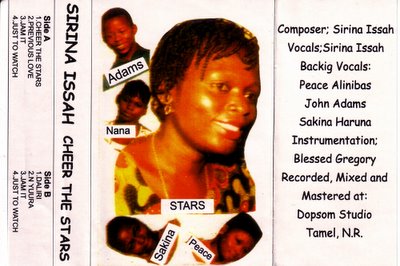

The first cassette release to include rap in Dagbani, the North's most commonly-spoken language, was a track on Sirina Issa's debut Cheer The Stars. The "Godfather" of Dagbani-language rap is Big Adams. Adams was only a kid when he was featured on Issah's incredibly surreal-sounding ode to Ghana's national football (soccer) team, the Black Stars. To me, this album is nothing short of genius. Primitive beats that are at once funky and cute, along with Sirina's almost grating vocals, make for a singular experience. Backing vocals by a ragtag cast of basically neighborhood kids make it sound like "outsider" music by people obsessed with early Prince and Stacy Q.

Considering how new to Northern ears these kinds of sounds were at the time, this recording is important. Down South, they'd been releasing plenty of records with hip, electronic beats for a long time, but the lyrics were almost always in Twi. With Cheer The Stars, Issah invented a new landscape for music in Tamale. This album was a hit up there, with the track featuring this new vernacular rapping hitting particularly hard. Recorded in 1993, released in 1994, people had been hearing rap in Twi for a few years now, here and there. But, for the youth of Tamale, rap in Dagbani was novel.

Below is the cassette cover, complete with spelling errors and amazing cut and paste design:

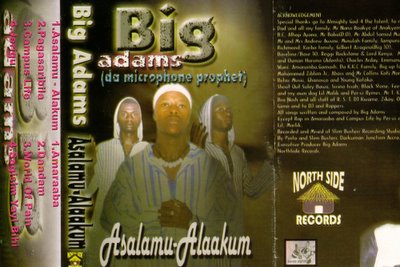

Big Adams evenutally put out his own debut on North Side Records a few years later. Nicknamed "Da Microhpone Prophet," Big Adams's name is unanimously invoked when discussing the roots of hiplife in the North. His album, entitled Asalamu-Alaakum, made clear the distinct identity he wanted for rap from the North (the phrase is a greeting used across the Muslim world).

This is the cover of Big Adams' first full-length. Note the Northern-style cloth, Muslim cap and prayer pose:

Big Adams today:

Watch a snippet of my interview with Big Adams, "Da Microphone Prophet"

The music stressed the melismatic vocal style found across the Sahel, something that brings closer to mind faraway Morocco or Egypt more than the predominately Christian Southern Ghana. Musically, Big Adams and his colleagues created a sound that blends equal parts higlife, indigneous praise singing (which utilize hourglass-shaped tension drums played under the arm with one hand), and Bollywood.

Why Bollywood? If you take a walk around any market in Northern Ghana, or Burkina or Mali for that matter, you'll find a good number of Bollywood videos and CDs for sale. For some reason, Bollywood has made headway in this unlikeliest of areas, where it is not uncommon get in a taxi or sit in a restaurant and listen to/watch Bollywood music/movies. Few in the South have interest in Bollywood, making this aspect of Northern hiplife a particularly unique element.

Again, the musical sensibilities relate more to the music of Mali and Burkina Faso, than of what you may hear on national radio. But, since radio became privatized throughout Ghana in the mid-1990s, Tamale-based stations promoted the new Northern hiplife songs. This music would never be heard or appreciated in the South, except in the handful of urban slums in Accra and Kumasi inhabited by Northerners.

More on all this to come...

Check out this article on Northern Music Awards in Tamale last December

Saturday, January 07, 2006

To Whom It May Concern, Hiplife Kinda Sucks...

People I met in Ghana, after listening to me explain what I was up to, often voiced concerns and opinions about the hiplife movement. If I wasn't hearing it from someone sitting next to me on the bus, I was getting complaints through the media: on the TV news reports; on the radio talk shows; in many of the magazines; basically, all over town I'd hear people discussing hiplife music, hiplifer youth, and the lyrics of the controversial song of the moment. Often you find a letter-to-the-editor like this one. This guy is worried about profanity in hiplife lyrics and its effect on Ghanaian youth. He gives us a laundry list of hiplife's good and bad contributions to society, making many of the statments I heard repeatedly from a variety of players in the industry. I also found regular, everyday people I discussed hiplife with often had passionate opinions on hiplife. Many I spoke with tended toward similar conclusions to that of this gentleman (despite most of them dancing to hiplife with the rest at funerals, engagements and other events featuring a DJ and sound system).

Sometimes I wonder how much of what I heard in my interviews were accepted lore and how much is actual independently though-out conclusions made by the individual. Probably a combination of the two since Ghanaians, like the rest of us, are confronted with mass media, and its embedded conclusions, at every turn.

Also, this guy, Maximus Ojah, writes great op-ed pieces in the various Ghanaian newspapers and online magazines. Here he is with some entertaining and insightful thoughts on hiplife in Ghana. This guy's writing is great. I love how he incorporates Ghanaian slang into his pieces while retaining an illustrative, articulate approach. In case you're wondering, the 'Osagyefo" he keeps addressing in his columns is none other than Ghana's founding father, Kwame Nkrumah. Osagyefo means "victorious leader".